We’ve been here once before. Did you forget how it ended?

The Last Time The 20s Roared

We all know what’s driving today’s record stock valuations.

Innovation, and of course, AI.

But what drove valuations the last time they reached levels almost as extreme as today’s?

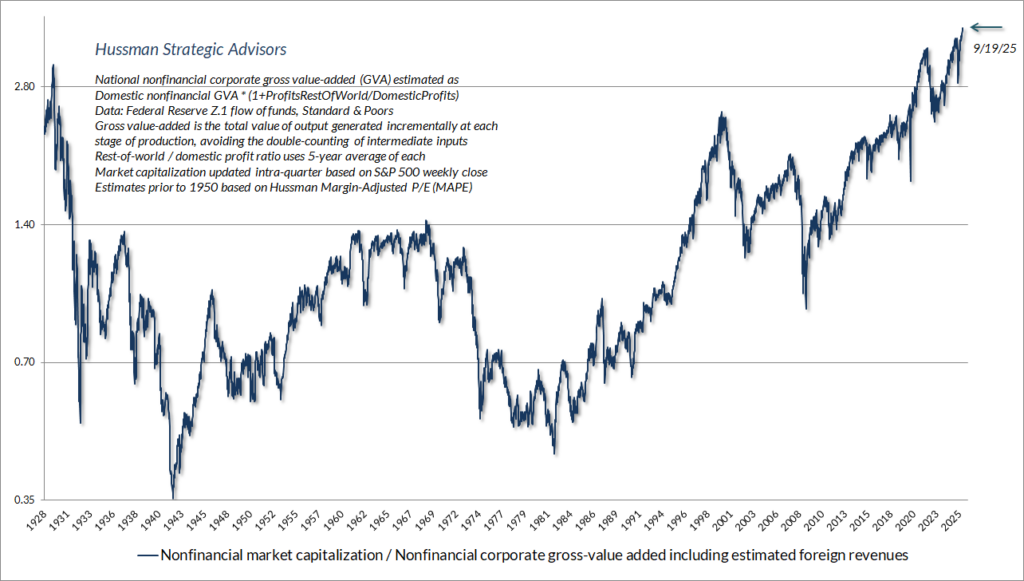

The chart below shows John Hussman’s stock market capitalization relative to corporate output.

We have been here once before. It was long ago…

It was way back in 1929.

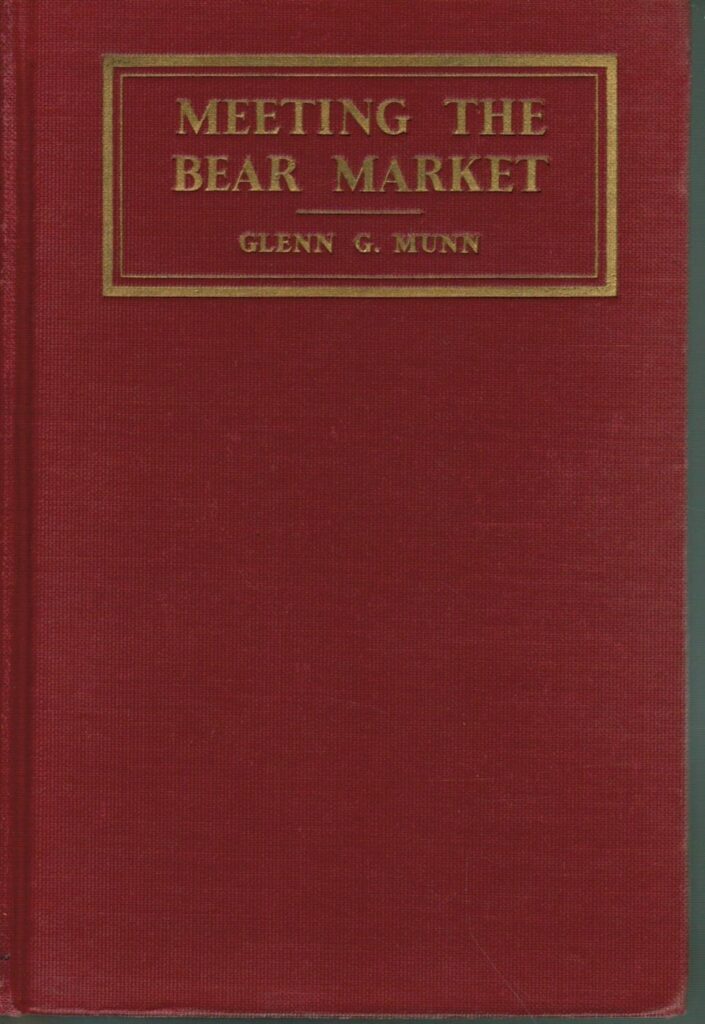

Meeting the Bear Market, written in 1929 and published in 1930, gives us a clue to why people got so crazy…

Electricity. Automobiles. Radio. Telephones. Airplanes. Chemistry.

Electric lighting, household appliances, asphalt paving, assembly lines, mass production, mechanized farming, refrigeration, elevators, air conditioning, skyscrapers, urbanization.

The League of Nations, promising world peace.

The Federal Reserve, promising to eliminate the business cycle.

National retail chains like Sears replacing the general store.

Professional management giving rise to corporate giants like General Motors, Standard Oil, and U.S. Steel.

Moving pictures, record players, and jazz to entertain the masses.

Consumer credit and advertising to seduce the consumer.

And Prohibition, keeping investors cold stone sober.

The last time the 20s roared, it was innovation.

Stocks were bid way out of proportion…

Because it was different that time.

And maybe it was.

But hey, today we have AI, so who even needs electricity?

AI promises to lift productivity,

reshape entire industries,

and what could be better for stocks than eliminating half of America’s white-collar workforce?

So read a little of what Glenn Munn wrote in 1929.

Just don’t forget to BTFD…

The book excerpt below is the inspiration for this article. All rights reserved by the original source.

MEETING THE BEAR MARKET

HOW TO PREPARE FOR THE COMING BULL MARKET

Glenn G. Munn 1930

“I saw a new heaven and a new earth … and the former things were unremembered”

From 1922 to autumn 1929, this country reared a colossal arc of prosperity. In creative achievement, volume of production, diffusion of wealth, and general well-being, cornucopias of the past paled into comparative insignificance. A new technology was flourishing – wizard dreams of laboratory and workshop were transfigured presto into actualities. New energies were unleashed. New methods replaced old. As the cycle proceeded, the tempo of trade and industry quickened; our fortunes advanced in rising crescendo.

In large measure, increasing prosperity was due to the alacrity with which American business management capitalized the rapid succession of scientific discoveries and technical inventions. It is no exaggeration to say that since the war our advance in industrial technology has been at a cumulatively accelerated rate – the accomplishment greater than for any similar period in history.

Experimentation, stimulated by installation of research departments and laboratories by aggressive manufacturing enterprises, led to the perfection of countless new devices and improvements in existing implements of production. Strides in building new and more efficient machinery were matched only by the development of a wide assortment of new consumable products susceptible of national and international market exploitation. Demand for perfected types of productive instruments and the growing number of enjoyable products created by a scientifically controlled industrial and commercial regime brought increasing profits to industry and a higher standard of material comfort.

Among the more prominent developments in the past eight years were those in aeronautics, radio, sound reproduction, chemistry, and electrical adaptations. Automatic machinery became general in practically all manufacturing lines where standardized duplicative processes predominate. Important improvements arrived in acoustics relating to talking machines and talking pictures. Television, color photography, and photograms became realities. Automatic refrigeration made important headway for commercial and household uses.

Improvement has been so rapid as to cause obsolescence of many machines and processes within a few years. Increased fuel utilization by railroads, utilities, and industrials effected large savings. Water-power development and super-power interconnections cheapened the cost of electric generation and distribution. Important changes occurred in the automotive lines, which, coupled with universal roadbuilding, enhanced the significance of bus and truck transportation. Electrification of homes and farms, and further application of electricity to new household devices, eliminated drudgery.

The chemical field was replete with new discoveries and adaptations, among which the production of textiles from wood-pulp base, fixation of atmospheric nitrogen, electric welding, bakelite, synthetic motor fuel, synthetic flavors and perfumes, continuous process in metal fabrication, adaptation of ferrous and non-ferrous alloys for specific purposes, were outstanding. Farming was immeasurably transformed through the use of power machinery, fertilizers, and application of newly found principles in horticulture and selective breeding.

There were changes in business technique. American genius has scored in organization as well as in solution of technical problems. Reference is made to coordination of sales and production, advertising and the development of revised principles of merchandising, as exemplified by the chain store, chain department store, mail order retail store combinations. Along with this came the consolidation of units in allied lines to effect stability and diversification, creation of new products, and new uses for old products. Internal organization improved with the mechanization of office equipment… [Book continues]